- Home

- Angela Cerrito

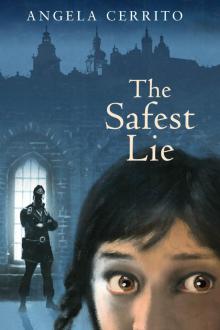

The Safest Lie Page 2

The Safest Lie Read online

Page 2

“The bread is for you, Anna,” Mama says.

“I can’t eat it all.”

“Yes,” Papa agrees. “You must.”

It’s always this way. Mama says that I need more food because I’m growing and Papa agrees with her every time. I bless the bread. “Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the universe, who brings forth bread from the earth.”

My parents fix their eyes on me, making sure I swallow every crumb. When I’m finished, they nod as if I’ve just completed my homework and done a good job on it too.

The next morning, before sunrise, there is a knock. Mama jumps out of bed and flies to the door. I see Jolanta’s face as Mama cracks it open. She passes Mama a small piece of paper and disappears. Mama leans back against the closed door. She doesn’t know that one of the men has woken up. He watches her. She doesn’t know that I’ve got one eye closed and the other eye fixed on her face. She unfolds the paper, brings it up to her mouth and gives it a kiss. I quickly shut my spying eye before she climbs into bed and lies down next to me.

Chapter 4

This morning the two men leave early. They take all of their belongings: two big packs that they haven’t opened, a rolled blanket and a pillowcase. I’ve seen them take a book, a comb and a pair of shoes from the pillowcase, but nothing else. The room feels bigger, but we don’t step into the empty space. Even though every trace of them is gone, that half of the room is assigned to them.

When Mama’s untangling my hair, she tells me I won’t be going to youth circle.

“I have to. I need to help.” It’s a quiet morning; there’s been no gunfire, no sign of a raid.

“Not today, Anna.” She taps my cheek and I turn my head to the light from the small window.

I hate the dangerous days. The days we must stay inside our room or rush off to one of the hiding places. “Please, Mama. There might be homework. There’s no sign of danger.”

I know as soon as the words slip out that I’ve made a mistake. Mama always says danger is everywhere. But she surprises me and agrees. “You’re right, there’s no sign of danger.” She lifts a new strand of my hair. “I have work for you here today.”

“Yes, Mama.” She didn’t say homework, so I know it’s not food. But what work could I do in our room? We’ve already rolled up the mat. Papa’s standing by the dirty window. We have no cleaner or rags to clean with, no broom to sweep the floor.

Mama taps my other cheek and I turn my head. If this were a real school day, back home, Mama would pull my hair tight and twist it into braids. Then she’d tie them at the ends with red or gold ribbons to match my school uniform.

When she’s finished with my hair, she closes her eyes like she always does. She’s thinking about home. I try to block out the picture of our old house, of Grandma and my cousins. Instead, I think of Sonia, already busy at work outside, and Halina and Marek, strong and healthy because of the shot they had yesterday. I should be helping them.

Mama pulls my hand. “Let’s sit.” She sits on the floor with her back to the wall and I sit beside her. “Today, Anna, you have a new name.”

“My name is Anna.”

“Right,” Mama says. “Your name is Anna. But, starting today, it’s not Anna Bauman. It’s Anna Karwolska.”

Papa turns from the window. “What have you done? I said I didn’t want this.”

Mama tilts her chin up at Papa. “It’s going to happen,” she says. “It’s going to happen.” She looks at me. “Your name is Anna Karwolska. Tell me your name.”

I glance at Papa. His shoulders slump and he moves back to the window.

Mama taps my leg. “Say it.”

“My name is Anna Karwolska.” The words are heavy and far away, like a stone thrown so far out into the lake that it is impossible to hear the splash.

I quickly learn a new name, address, birthday and the names of Anna Karwolska’s parents. I even learn her parents’ birthdays. Mama switches to French and asks the same questions over and over. And then in German, she makes me repeat the new name and all of the information again and again.

It takes concentration to remember every detail, to answer Mama’s questions quickly and perfectly.

Papa turns away from the window and looks down at us.

“How old are you?” Mama asks me in German.

“Acht.” Eight, I answer, though I’m really nine. Anna Karwolska is still eight. “Now may I go to youth circle? I know all the answers.”

Mama shakes her head. “Yes, you know the answers, but you must speak every word like you believe it. Make me believe it.”

How can I make her believe so many lies? One of Grandma’s sayings comes to me and I blurt it out without thinking. “The truth is in sight. The lie is behind the eyes.”

Mama locks her eyes on me and responds with another favorite saying of Grandma’s. “The truth has many faces.” Then she sighs and says, “Please only Polish or German. Not Yiddish; it’s too dangerous.”

Only Jewish people speak Yiddish. When I was three years old, I used to call it Grandma’s language because everyone spoke to Grandmother in Yiddish. I take a breath and prepare to answer more of Mama’s questions, but we are interrupted by a light knock on the door. Everyone knocks lightly, so the people inside know it’s not a soldier at the door. Papa opens it and Halina rushes in. Marek follows his sister like a shadow.

Halina greets my parents. When she turns to me, she begins to sob.

“What is it? What’s wrong?”

“Jolanta said she could help Mrs. Rechtman escape. She has papers and a safe house outside the ghetto.”

I want to sob too, to stomp my foot like I did when I was small. I wish I could yell No! No! No! No! But it is impossible for me to raise my voice. I know I can’t draw attention to myself. That’s one way people get killed. Halina’s sobs are quiet. Her tears soak into my shirt.

If Mrs. Rechtman leaves, we will be miserable. My mind leaps over the guards and outside the gate. Jolanta can do anything. She sneaks food and medicine into the ghetto and she can sneak things—people—out. Mrs. Rechtman will have food. She will be safe. Halina wipes her face. I put my hand on her shoulder. “Don’t cry. It’s for the best,” I tell Halina. “When will she leave?” I worry for a moment that I’ve missed her, missed my chance to say good-bye.

Halina shakes her head. “She won’t go. She told Jolanta that she won’t leave until all of the children are safe.”

Of course, Mrs. Rechtman would never leave us.

When Halina leaves, Mama unrolls the mat. Two years ago, when I lived at home, I was too big for naps, but here everything is different. I don’t mind. Sometimes sleep can take away the feeling of being hungry.

Even while I am asleep, Mama shakes my shoulder and asks, “What is your name?”

“Anna.”

“Anna who?”

By the third time, I answer her without hesitating: “Anna Karwolska.”

Chapter 5

In three days Mama has her wish. I am able to be Anna Karwolska all day. It is as automatic as saying my prayers.

I wake from a deep sleep, uncomfortable. Not from sleeping on the floor or Mama lying beside me, I’m used to that. It’s because Papa’s leaning against the wall with his eyes glued on me tightly, as if I’ll disappear if he looks away.

I sit up and stare real hard back at him. When he sees I’m fully awake, Papa holds out his hand. I take it and stand. He barely glances at the sleeping strangers in our room as we walk to the window. I lean into Papa and we stare up at the moon. I put my hand on the cool window and Papa surprises me by tracing his finger around it.

He surprises me again by speaking in a calm whisper. It’s a poem.

“The brightening flame of truth pursue,

Seek to discover ways no human knows.

With every secret now revealed to you,

The soul of man expands within the new.”

Papa talks on and on. I don’t understand it all, but I love the way his voice,

so quiet, fills the room. The final line is about stars fading into the night. Papa’s voice, still quiet, is strong, strong enough to climb into the sky and whisper to the stars.

Chapter 6

The men who share our room leave early each morning. They stay out all day and only return in the evening to sleep. But we know they could show up at any time. Papa surprises us by saying he is going for a walk. He hardly leaves the room anymore.

Papa returns a short time later with a carrot. He leans his back against the door because it doesn’t lock. We silently pass the carrot around, each of us taking one bite. Mama barely scrapes the carrot against her teeth. I look to Papa. He always insists that she eat. But I catch him doing the same thing. The way he scrapes the carrot sounds like a bite, but there is very little for him to chew. I take a small bite and pass the carrot to Mama again.

I know about surviving in the ghetto. And I know about people who try to get out. They need fake papers, fake names, entire fake identities. Mama wants me to be Anna Karwolska, but she hasn’t told me when we will leave or where we will go.

“If I’m Anna Karwolska, are you her mother? Is Papa her father?”

“I know all about Anna Karwolska’s mother,” Mama says. “And your father knows all there is to know about her father.”

The carrot is back around to me again. “But are you her mother? Is Papa her father?” I take another small bite.

Papa holds the carrot in his hand. I study the small scar on the side of his finger. Mama nudges him to eat. “It’s not time to talk about this, Anna.” Her voice is low. “It will be time, soon enough.”

There is a light tap on the door. “Open your mouth, Anna.” Papa holds out the last bit of carrot to me. I do as he says and he pops it into my mouth. Papa opens the door.

Jolanta steps in. Without a greeting, she places a package wrapped in brown paper in Mama’s hands. She looks at Papa and says, “I will need every address. Use the inside of the paper packaging.”

Papa holds out his hands, helpless. Jolanta nods and pulls two sharp pencils from her coat pocket. Papa’s eyes widen as he stares at the pencils in his palm. I can’t remember the last time I saw a pencil. Perhaps in Mrs. Rechtman’s school, so long ago. At home, Papa always had a pencil in his hand and usually wore one over each ear as well. When we first moved to the ghetto we had a big box full of pencils and a shelf full of books and a kitchen table with four chairs and an oven and . . .

To Mama, Jolanta says only one word, “Hurry!” before she dashes out the door.

Mama tucks the package under her coat out of sight and takes me by the hand. We walk four blocks and turn up the walkway to Anton’s house. Anton used to help Papa make furniture. His wife answers Mama’s tap at the door. Anton is soon at her side. The house is packed with people.

Mama offers him two carrots for a basin of water. We follow Anton deep into the house, down a long hallway. One or two families are crowded into each room. At the end of the hall is a small bathroom without any fixtures. A pipe sticks out of the wall where there once was a sink. There is a hole where the toilet used to be. Mama hands over the two carrots, and in a short while Anton’s wife brings us a big bowl of cold water and a cloth. Mama closes the door and hands me the wet cloth. I drape it over my face, tilting my head up, and stop to enjoy the moment.

“Hurry, Anna,” Mama urges. Though there isn’t any soap, the wet cloth erases the dirt and dust from my skin like magic. For the first time in weeks, my arms, my legs, even my hair feels clean and light. When I finish, Mama says, “Get dressed quickly and be sure to cover your hair with your scarf.”

Back in our room, Mama bites the material at the bottom of her shirt and tears off two small strips of cloth. Papa stands with his back to the window, watching as she pulls my hair into two tight braids and ties them with the strips of faded pink material. Mama unwraps the package from Jolanta. Inside is a new school uniform. My hands reach out to stroke the dark blue skirt. It has been so long since I’ve seen something so new or so clean. Mama looks up at Papa. “She must get dressed quickly.”

Papa takes the brown paper and leaves the room. I slip into the new clothes. The shirt is so new and stiff, I have to force each button through its hole. The uniform is big and long; I feel like I’m wearing a costume. I stick my feet into my shoes as Mama opens the door for Papa. He takes one look at me and folds me into his arms.

He shows Mama the lists of names and addresses he’s written for Jolanta. “I need the address in Lodz,” he says.

Mama’s hand goes to her pocket. She pulls out Grandma’s letter, takes a pencil from Papa and hands both to me. “Anna, your grandmother has printed the return address here on the envelope. Copy it, letter for letter, right here.” She points to the bottom of the brown paper.

I nod and sit down on the floor to write. Grandma’s printing is much neater than her handwriting. I can understand her letters. It has been months since I held a pencil, but I write Lodz, Wolborska 24 under my grandfather’s name. It almost makes me happy. As though they will see the writing and know it is from me.

“Last word,” says Mama, pointing to Grandma’s address.

I nod, bite my bottom lip and print getto below the street name. For a moment I can’t find my breath. My grandparents, my aunts and uncles, my cousins . . . Jakub. They are not only far away, but in a ghetto. Just like us.

I give the pencil and paper to Mama, but keep Grandma’s letter. It is the first one she sent to us. “Please, may I read it?”

Mama is silent, surprised. I don’t like reading Grandma’s letters. The first is all bad news. The other two are even worse. Still, I unfold the thin papers and steady my eyes on Grandma’s scribbles. Her handwriting makes some letters pointed where they should be curved. In a few moments, my eyes adjust and I can read Grandma’s writing as easily as the words in my first reader.

This letter is about my grandparents leaving their home. I read how they were forced to leave everything: their furniture, their dishes, their horses and even their old dog, Felek.

I stand and give the letter back to Mama. Papa hugs me once again. As soon as he lets go, Mama kneels in front of me. “Your name is Anna Karwolska.”

“I know.”

“Your parents are dead.”

“What?”

“Your parents, Anna Karwolska’s parents, are dead.”

My throat tightens as if I’ve swallowed a stone. Papa’s face burns red. “Is this necessary? Must you be so harsh?”

Mama stands to face him. She places her hands on her hips and for a second she looks bigger. I see a flash of Mama from before we moved into the ghetto, before she grew so thin and so pale. “This is nothing,” she says to Papa. “I must be even harsher.” Mama’s eyes lock onto mine. “Most important, you are not Jewish.”

“Yes I am.”

“You are Anna Karwolska. Anna Karwolska is not Jewish. Say it. Say, ‘I am not Jewish.’ ”

The words taste rotten on my tongue but I whisper, “I am not Jewish.” If only Mama would hug me, the way Papa did. If she would just tell me that I am doing a good job.

“Always remember, you must never admit that you are Jewish. Do you understand?”

I nod.

“Anna Karwolska hates Jewish people. She would never play with a Jewish child. She would never help a Jewish adult. Say it. Say, ‘I hate all Jews.’ ”

“Mother, no!”

“Your mother is dead. Say it. Say, ‘I hate all Jews.’ ” Mama’s voice is like a growl.

I take a step back. “No.”

“Say it.”

“You’re not my mother. You can’t make me say anything.” My body feels cold and heavy and far away.

“I love you,” says Mama, my real live mother, Anna Bauman’s mother. Mama blinks back tears. “I only want you to be safe.”

I step forward and Mama’s arms tighten around me. They aren’t light like butterfly wings. They’re strong, the strongest thing in the world.

Chapter 7

Someone taps on the door three times. Before Papa can answer it, the door opens. Jolanta sticks her head inside and says, “Be ready.” The door closes quickly and silently.

Mrs. Rechtman visits next. Her eyes dance between Mama and Papa. She nods to me. “You look very nice, Anna.” Mrs. Rechtman turns to Papa next. “I have to take her now.”

I’ve known from the start that learning to be Anna Karwolska was preparing to leave. But now Mama’s words come back to me. Your parents are dead. This can’t be right. I look up at Mama. “You’re not coming with me?” She stares deep into my eyes as if she can see something more—more than me. But she’s silent. “You and Papa, you’re not coming with me?”

Mrs. Rechtman says it again. “I have to take her now.”

Something in my brain screams, “No!” My shoes are frozen to this spot, to this room I share with Mama and Papa. Mama’s arms are around me again. She seems to stretch big enough to swallow me whole. Papa reaches his arms out. All that’s left of me for him to grasp are my hands. He’s got a tight hold to them as if he’ll never let me go.

I can’t hear my shouts over the cries of my parents. Mrs. Rechtman pulls their arms away and separates me from Mama and Papa. In the next instant, I am out the door.

I’m not crying. But I’m not breathing either. My chest is so tight, it hurts to breath. Mrs. Rechtman tosses a dirty smock over my head to hide the new school uniform. “Be silent. Stay close to me.”

She hurries down the stairs and out into the crowd. People bump and push against each other on the streets, but I stay right on her heels, letting no one between us. On and on we walk. Mrs. Rechtman seems to gain speed with every step she takes. She doesn’t look back.

There is no end to the number of children begging for bread. Round eyes and open hands reach out to me as I go by. I think of Halina; I didn’t say good-bye. One small boy is holding a sock. He waves it at me as I pass. “Bread, please. Bread.” I’ve seen children begging on the street before, but I had no idea there were so many.

The Safest Lie

The Safest Lie